I can look out my window most school days and see that our favorite pastimes — all varieties of sport from frisbee to rugby — thrive on the John Carroll University campus as they have for more than a century. Very little else, however, has gone unchanged in that time, and that’s especially true of college athletics which continues to undergo seismic upheaval.

A couple of weeks ago, on June 23, 2022, we marked the 50th anniversary of the passage of Title IX, a federal civil rights law that gave women athletes the right to equal opportunity in sports in educational institutions from elementary schools to colleges and universities.

Title IX dramatically expanded women’s athletic programs and participation at the high school and college level. In 1971, fewer than 30,000 women played sports at the college level, representing just 15% of all student athletes. Many colleges offered few or no women’s teams.

Today, nearly 225,000 women participate in NCAA college athletics, about 44 percent of the total. At the Division III level, more than 83,000 women compete for championships across 14 sports.

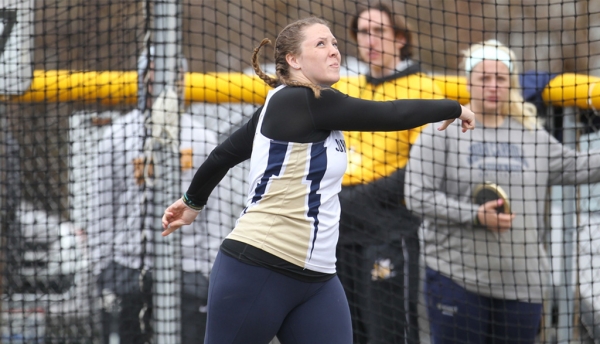

A month before the Title IX anniversary, four John Caroll women (Cameron Bujaucius, Erica Esper, Olivia Hurtt, and Kelsey Dunn) competed at the 2022 NCAA Division III Outdoor Track & Field Championships. Just as impressive, they exemplify the DIII principle of high academic performance, earning Dean’s List and National Honors Society recognition. Senior Olivia Hurtt will enroll at the University of Florida School of Veterinary Medicine in the fall.

One Year of Name, Image, Likeness

At nearly the same time of the Title IX anniversary, colleges across the country marked one year since the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in NCAA v. Alston, which opened the door for all student athletes to benefit from Name, Image, Likeness (NIL) deals.

Name, image and likeness (NIL) are three elements that make up the legal concept known as “right of publicity.” The right of publicity, sometimes called “personality rights,” is an individual’s right to control and profit from the commercial use of his/her name, image or likeness.

Ohio became one the first states to pass a Name, Image, Likeness law for its colleges and universities on June 28, 2021. The law says that all 13,800 NCAA athletes in Ohio across 45 NCAA schools have the right to earn compensation for their name, image and likeness — as long as it does not involve association with marijuana, drug, alcohol, adult entertainment, casino, or gambling.

NIL Ecosystem

An entire ecosystem continues to emerge around NIL, involving digital platforms that broker deals between athletes and sponsors, booster collectives that pool money and deals, and plenty of bootstrap ingenuity among athletes pitching themselves to potential sponsors.

Commercial spots, autograph signing, creation of digital NFT collectibles, special issue merchandise and appearance deals are just a few examples of how NIL has played out so far. Sponsors are only now beginning to ask about how to measure the return on their investment.

Many questions linger.

- Should colleges and universities mobilize and provide student athletes with additional financial coaching, brand and marketing mentoring, tax preparation and other non monetary NIL support?

- Does NIL disproportionately benefit athletes at rural and small town schools where college athletes enjoy a larger profile, or at urban schools where access to corporate connections and internships represent a more immediate and tangible benefit?

- Will NIL create a slippery slope that sees boosters, sponsors, and athletes not just brokering promotion deals, but shopping NIL promises to influence recruiting and transfers?

- Will NIL exacerbate or alleviate existing inequalities that allow higher-income high school athletes to play college sports at more than twice the rate of their lower income peers?

Most of the deals and media attention has flowed to the Division I Power 5 and higher profile revenue sports and athletes. Year two NIL compensation is expected to reach $600 million (average of $16,074 per athlete), with women’s basketball, volleyball and softball trailing only men’s football and basketball.

Division III Future

But as the tide and time wait for no man, NIL will surely change Division III athletics. Already, the industry estimates that DIII will see more than $58 million in NIL compensation by year two. Profit-making online platforms and NIL conferences encourage athletes from all divisions to jump in and self promote, holding up examples of “influencer” athletes who leverage tiktok and instagram followings for NIL cash.

We’re watching a conflagration of two worlds — the $19 billion per year college sports entertainment industry and a set of Division III priorities that work to minimize conflicts between academics and athletics, and that aim to integrate student athletes into a larger community rather than amplify any of their athletic success into a larger-than-real-life presence or social standing.

NIL + Character

NIL advocates celebrate the “democratization of college athletics.” At its core, the Supreme Court ruling gives control, rightfully, to the individual athlete on how they are to be associated with their performance and reputation.

How do we, as a Jesuit community, best support our hard-working, highly accomplished athletes? I turn to the essential characteristics of a Jesuit education for guidance.

When we speak of “formation of the individual,” our concern extends to how young people will prosper and thrive within the human community, in the service of others “for the praise, reverence, and service of God.”

In that light, can we imagine a name, image and likeness movement that recognizes the importance not just of one’s self-promotion potential, but one’s character — who you are at your very core — and works to align opportunities accordingly?

Among the more than 60 NIL collectives that have formed around major Division I programs is something called the Cohesion Foundation, a group of high profile Ohio State athletic alumni who seek to “foster opportunities for current student-athletes to support charities in an effort to build a stronger community.”

Could similar efforts curb the more narcissistic temptations and excesses of NIL? Rather than a race to gather social media followers and a shallow exercise in “charisma” points, could NIL deals link financial support to community building, and restore perspective?

As Jesuit educators, we look to uphold a set of values leading to life decisions that go beyond “self” — that favor concern for the needs of others. In the current NIL context, “cura personalis” (concern for the individual person) needs to weigh both the legal right of student athletes to claim agency over their individual publicity, and some concern for the collective.

Could we imagine various “tip sharing” arrangements where John Carroll athletes consider how to leverage their NIL rights, while also reflecting on the highest need and good for any money raised? Can relationships between athletes — with the potential for lifetime relevance — be prioritized over the success of a few at the expense of the many?

Exceptional Ordinariness

The exceptionalism of our students, I believe, remains grounded in their quiet dedication to academic growth and personal formation, rather than on any fleeting bit of fame or claim of “influencer” among an audience of people largely unknown to them.

I’d like to think that in 20 years, the casual exchange of frisbees between athletes and non-athletes will do more to mature all John Carroll University students and prepare them for the work of integrating into companies and communities than a one-time injection of NIL money. In the long view of a well-lived life, NIL represents a brief chapter — albeit one that could render one’s character structure more brittle or more elastic and durable, depending on the choices an individual makes.